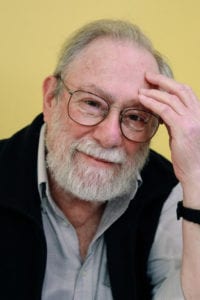

We are deeply saddened to share news of the death of beloved poet Marvin Bell. Bell—the first Poet Laureate of Iowa, a National Book Award Finalist, and professor of literature—died peacefully at his home in Iowa City, IA on December 14, 2020. He was 83.

Bell is the author of over 20 volumes of poetry, including Incarnate: The Collected Dead Man Poems (Copper Canyon Press, 2019), Vertigo: The Living Dead Man Poems (Copper Canyon Press, 2011), and Stars Which See, Stars Which Do Not See (1977), which was a finalist for the National Book Award in Poetry. In an interview with The Iowa Review Marvin Bell stated, “Poetry gave me a way to express everything at once. That is, it gave me a method by which to say more than words can say.”

Known for mining the intersection of philosophy and poetry, Bell’s work brings meaning and discovery to daily life. In his introduction to Incarnate: the Collected Dead Man Poems, David St. John writes, “No voice in our poetry has spoken with more eloquence and wisdom of the daily spiritual, political and psychological erosion in our lives; no poet has gathered our American experience with a more capacious tenderness—all the while naming and celebrating our persistent hopes and enduring human desires.”

Bell wrote about a vast array of topics but he is most known for creating the character of the Dead Man, a trickster character that he has written about for more than thirty years. The Dead Man uses his all-knowing voice to interrogate the joys as well as the catastrophes of the personal and the political—everything from wartime to peacetime, to Bob Dylan, fungi, and not sleeping. In speaking about Incarnate: The Collected Dead Poems for The New York Times, Naomi Shihab Nye states, “While the Zen admonition—Live as if you were already dead—may embody a lively challenge, these poems, too, tip their hats with greatest respect and fanciful care for the living mystery that holds us all.”

Michael Wiegers, Bell’s longtime editor at Copper Canyon Press, said, “Marvin Bell came to Copper Canyon Press over thirty years ago. His support of Copper Canyon over the decades has paved the way for so many of the poets we publish now. It’s been a true honor to publish such an inventive and curious poetic voice—one who has managed to change the landscape of American poetry forever.”

Wiegers went on to say, “He was one of the first poets I met when I started at the press, and while I always recognized him as a tremendous and imaginative poet, he was also an unrelenting friend and advocate for poetry. Bell made certain to support the oddball originals and always strived to push poetry forward. I will miss his stories, his trivia and his faithful friendship. The Press is indebted to his generous influence.”

Marvin Bell was born in New York City in 1937, and grew up on Long Island. He holds a BA degree from Alfred University, an MA from the University of Chicago, and a MFA from the University of Iowa. Bell’s debut collection of poems, Things We Dreamt We Died For, was published in 1966 by The Stone Wall Press, following two years of service in the U.S. Army. Since then Bell has published over 20 collections of poetry. He taught for forty years for the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, retiring in 2005 as Flannery O’Connor Professor of Letters.

Bell’s final collection of poems, Incarnate: The Collected Dead Man Poems, was published in 2019 by Copper Canyon Press.

“Poem After Carlos Drummond de Andrade”

by Marvin Bell

“It’s life, Carlos”

It’s life that is hard: walking, sleeping, eating, loving, working and

dying are easy.

It’s life that suddenly fills both ears with the sound of that

symphony that forces your pulse to race and swells your

heart near to bursting.

It’s life, not listening, that stretches your neck and opens your eyes

and brings you into the worst weather of the winter to

arrive once more at the house where love seemed to be in

the air.

And it’s life, just life, that makes you breathe deeply, in the air that

is filled with wood smoke and the dust of the factory,

because you hurried, and now your lungs heave and fall

with the nervous excitement of a leaf in spring breezes,

though it is winter and you are swallowing the dirt of

the town.

It isn’t death when you suffer, it isn’t death when you miss each

other and hurt for it, when you complain that isn’t death,

when you fight with those you love, when you

misunderstand, when one line in a letter or one remark in

person ties one of you in knots, when the end seems near,

when you think you will die, when you wish you were

already dead—none of that is death.

It’s life, after all, that brings you a pain in the foot and a pain in the

hand, a sore throat, a broken heart, a cracked back, a torn

gut, a hole in your abdomen, an irritated stomach, a

swollen gland, a growth, a fever, a cough, a hiccup, a

sneeze, a bursting blood vessel in the temple.

It’s life, not nerve ends, that puts the heartache on a pedestal and

worships it.

It’s life, and you can’t escape it. It’s life, and you asked for it. It’s life,

and you won’t be consumed by passion, you won’t be

destroyed by self-destruction, you won’t avoid it by

abstinence, you won’t manage it by moderation, because

it’s life—life everywhere, life at all times—and so you

won’t be consumed by passion: you will be consumed

by life.

It’s life that will consume you in the end, but in the meantime . . .

It’s life that will eat you alive, but for now . . .

It’s life that calls you to the street where the wood smoke hangs,

and the bare hint of a whisper of your name, but before

you go . . .

Too late: Life got its tentacles around you, its hooks into your heart,

and suddenly you come awake as if for the first time, and

you are standing in a part of the town where the air is

sweet—your face flushed, your chest thumping, your

stomach a planet, your heart a planet, your every organ a

separate planet, all of it a piece though the pieces turn

separately, O silent indications of the inevitable, as among

the natural restraints of winter and good sense, life blows

you apart in her arms.