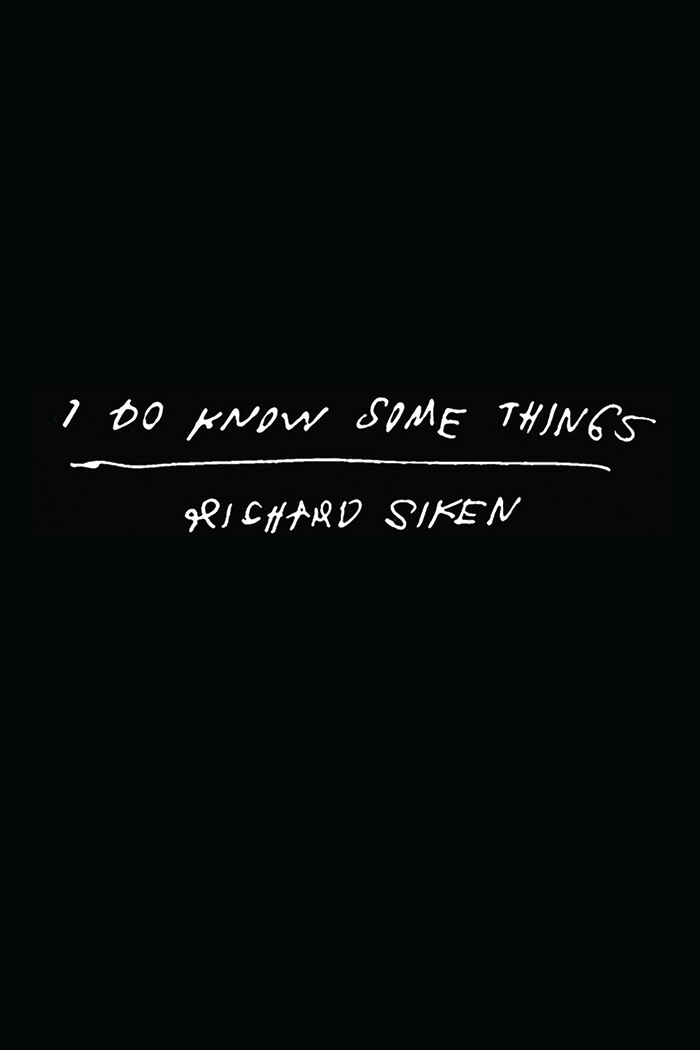

Richard Siken’s long-anticipated third collection, I Do Know Some Things, navigates the ruptured landmarks of family trauma: a mother abandons her son, a husband chooses death over his wife. While excavating these losses, personal history unfolds. We witness Siken experience the death of a boyfriend and a stroke that is neglectfully misdiagnosed as a panic attack. Here, we grapple with a body forgetting itself—“the mind that / didn’t work, the leg that wouldn’t move . . . ”. Meditations on language are woven throughout the collection. Nouns won’t connect and Siken must speak around a meaning: “dark-struck, slumber-felt, sleep-clogged.” To say “black tree” when one means “night.”Siken asks us to consider what a body can and cannot relearn. “Part insight, part anecdote,” he is meticulous and fearless in his explorations of the stories that build a self. Told in 77 prose poems, I Do Know Some Things teaches us about transformation. We learn to shoulder the dark, to find beauty in “The field [that] had been swept clean of habit.”

ISBN: 9781556596247

Format: Hardcover

Cover Story

My boyfriend did not die in 1991. I told a lie and it turned into a fact, forever repeated in my official biography. He died on Christmas Day, 1990, when his family disconnected the mechanical breathing machine. He was a composer in the school of music. We were working on a piece for voice and strings. I liked writing the words under the whole notes, hyphenating them to make them last. I liked sitting on the bed in his apartment, writing on the sheet music—bigger paper, thicker, how it sounded when it fell to the floor when we got tired. It was winter break, friends in town, we hopped from party to party, catching up but separately. It was late, the night was clear, the roads were empty. The four of them were sober, the driver in the other car was not. I was a few miles away, in a bar, waiting. When the bar closed, I left him an angry message for standing me up. A few hours later, a friend called and told me. He suggested I break into the apartment and start removing things before the family arrived. For several minutes I didn’t understand, then—evidence. He hadn’t told his family and it didn’t seem right to tell them now, to suggest that they didn’t really know him. I drove in the darkness between the accident and dawn. I climbed through the window. I couldn’t figure which things looked suspicious and which things would be missed. I was sloppy, rushed. I grabbed the wrong sheet music.