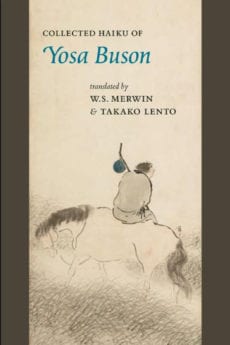

Yosa Buson

Today the haiku master Yosa Buson (1716–1783) is regarded as one of the greatest Japanese poets. Yet for a century after his death his work was in eclipse, overshadowed by the fame and popularity of Bashō. That all changed with Masaoka Shiki’s treatise Haiku Poet Buson (1896, revised 1899), in which he analyzed Buson’s haiku, in part, from the viewpoint of modern realism. Shiki acknowledged Bashō’s “reputation as the incomparable haiku poet.” Then he made the startling declaration that Buson is “equal to, or even surpasses Bashō.” At the time Japan was in the process of transforming itself into a modern nation, and haiku seemed like a relic of the past. Shiki took Buson as his inspiration in establishing and leading a reform movement that successfully revived haiku as a viable poetic form for the twentieth century. This was actually the second time Buson had been central to reviving the art of haiku. In his own lifetime, when verse writing was too often treated as a social game, he himself had led a movement to return to the aesthetics of Bashō. Buson deeply respected and paid homage to his great predecessor throughout his life, but his poetry is utterly his own in its materials, themes, and voice. He was a major artist as well as a master poet, and his powers of observation are evident in his verse. He is uniquely carefree and unbound by convention, conveying the realities of life with immediacy and warmth. His stated aesthetic principle was “use the commonplace and transcend the worldly.” His achievement in Japanese poetry extends beyond haiku. Buson also wrote free-form poems that blended Japanese and Chinese verse styles. These are now known as haishi, a term applied to them in the twentieth century. Some say that they are forerunners of Japanese modern poetry, a hundred years ahead of their time.